"The camps ... are as

different in their form

as the owners are in their

dress ..."

Shades, Sheds, and Wooden Tents,

1775-1782

Soldiers during the Revolutionary War often built makeshift shelters to cover themselves when tents or buildings were unavailable. American soldiers had a number of names for these dwellings, such as "brush Hutt," "bush housen," "hemlock bowhouses" (i.e., huts made of hemlock boughs), and "huts [of] brush and leaves." Some terms denoted similarly-formed shelters, while others described a distinctly different type of construct; all those named above were enclosed lodgings, with frames made of cut trees or tree limbs, covered with leafy branches or pine boughs. Several other appellations denoted shelters similar to brush huts or huts made of brush and/or boards under their definition: "booth" seems to have referred to a particular form of brush hut, and was perhaps the American term for an open lean-to (shaped like a Civil War shelter-half); sheds were similar in construction to brush huts, but covered with different materials, such as milled lumber, fence rails, cornshocks, or straw; and wigwam was a predominantly British term, encompassing any type of soldier-built ad hoc shelter. A fourth type was the bower or "shade," a flat-topped structure used primarily for protection from the sun, though several references seem to indicate bowers being constructed as lean-tos for overnight shelter as well as shade.1

In this part of our study we will examine bowers and sheds built by both sides in the War for Independence and British soldiers' widespread use of brush huts (wigwams).

"Not a bush to make a

shade near [at] hand ..."

Bush Bowers,

"Arbours," and "Shades," 1776-1782

For our purposes, bower is meant to refer to a flat-topped, leaf-covered temporary structure used primarily for shade rather than overnight lodging. Also known as bowries, shades, or arbors, they came in many sizes and normally were comprised of four forked poles, or saplings, for support (one at each corner) and a roof of wooden poles topped with a layer of leaf-covered branches or pine boughs. They ranged from small lean-tos, some perhaps less than five feet high, to large and elaborate shades high enough to stand under. Bowers were used by both officers and common soldiers during the war, usually for shade in warm weather (with or without tents), sometimes as sleeping quarters, and in other instances for special entertainments given for, and by, officers.

FIG 15. "The Officers of the Regt. are desired to attend tomorrow at 10 OCIock at Colonel Febigers Bush Arbour to settle their Ranks." Officer's shade, built by Helms' Company, 2d New Jersey Regiment, Monmouth Battlefield State Park, June 1995.

"An elegant shade ..."

Officers' Bowers

The officers of the Continental Army occasionally used bowers, usually in conjunction with tentage used for sleeping quarters; these shades commonly functioned as outdoor office, dining area, and meeting place (FIG 15). Three passages have been found showing Virginia officers using such shades. The earliest occurrence was in June 1776 at Norfolk, where an order was issued for "A Fatigue of a Sergeant and six men to Erect an Arbour over the Commanding Officer's Barracks, as well as the other Officers who may desire it." (In this case it is likely the "Barracks" referred to were tents.)2

While not overtly mentioned in the next two incidents, the use of shades in conjunction with tents is inferred as the army had moved from winter quarters and was encamped. Eleventh Virginia Regiment orders, 27 May 1777: "Camp Middle Brook [New Jersey] ... The Officers of the Regt. are desired to attend tomorrow at 10 OClock at Colonel Febigers Bush Arbour to settle their Ranks." A few months later, in Pennsylvania, Capt. John Chilton, 3d Virginia Regiment, mentioned a similar instance. Chilton jotted down a series of sums in his diary, under which he noted, "The above was furnished by Majr. Wm Washington which I paid him at Colo. Marshalls Arbour 22d. Augt. 1777 Cross roads." The final reference to bowers being used in this manner comes from Joseph Plumb Martin, who related that near West Point in l782 his "captain's marquee had a shade over and round the entrance."3

Alternatively, bowers were constructed to provide a place under which a special entertainment or worship service could take place. One such was constructed during Maj. Gen. John Sullivan's Indian Campaign in September 1779. That bower was used by Brig. Gen. Edward Hand to host an entertainment given for the officers of his brigade on the occasion "of Spain Declaring war against Great Britain and of the late generous Resolution of Congress of raising the Subsistence of Officers & soldiers of the Army." A lieutenant in the 4th Pennsylvania related the circumstances:

The officers of each Brigade assembled and Supped together (excepting Gen. Poors) on their ox and five gallons of spirits and spent the evening very agreeable. The officers of our brigade assembled at a large bower made for that purpose Iluminated with 13 pine [k]not fires round and each officer atended with his bread knife and plate and set on the ground Genl. Hand at the head & Col. Proctor at the foot as his officers suped with us in this manner.4

During the same campaign a more ambitious repast took place in July near Forty-Fort, Pennsylvania. Although described as a "booth," this term was sometimes used to describe various shelters; from the context it is evident a bower was being used.

This day General Poor makes an elegant entertainment for all the officers of his brigade, with a number of gentlemen from other brigades, and from the town. Gen. Hand and his retinue were present. The dining room was a large booth, about eighty feet in length, with a marquee pitched at each end. The day was spent in mirth and jollity. The company consisted of upwards of one hundred.5

The following year, in northern New Jersey, a similar affair was described by a surgeon in Jackson's Additional Regiment: "10th. [July 1780]... We erected a large arbor, with the boughs of trees, under which we enjoyed an elegant dinner, and spent the afternoon in social glee, with some of the wine which was taken from the enemy when they retreated from Elizabethtown."6

During the 1781 Virginia Campaign a number of accounts noted bowers used for several purposes. While the British army was either at some distance or preoccupied with fortifying Yorktown, there seems to have been sufficient leisure afforded American officers for some pleasant diversions. Massachusetts lieutenant Ebenezer Wild wrote,

23d. [July] Exceeding pleasant weather. At 3 o'clk I dined with Genl. Muhlenberg, about one mile from his quarters, under a large bowrey, built for that purpose on the bank of the [James] river.

14th. [August] The officers of the Regiment dined together under an elegant bowry built (in the rear of the Regiment) for that purpose.7

It is evident that with some ingenuity, and given sufficient material, a rather large structure could be constructed in a relatively short period of time. Unfortunately, the size of the "large bowrey" was not noted; it is doubtful that it rivalled the one near Forty-Fort in 1779.

FIG 16. "As soon as the tents are Pitched and the Bowers made, the Troops will attend to the Claning and repearing their Cloths & Arms. Racks or Forks are to be fixed in front of each regt to bear the arms against." Reconstruction of a brush bower, built by the author and Charles LeCount at Daniel Boone's Homestead, 20-21 May 1995.

Toward the end of August 1781 two Pennsylvania officers observed another use for bowers. An anonymous officer wrote that he "attended Divine worship on the banks of the River under an elegant shade." Capt. John Davis on the same occasion was more descriptive: he noted the same structure as being "a shade of Cedars."8

At West Point in 1782, a bower of mammoth proportions was built to accommodate festivities honoring the birth of Louis XVII, Dauphin and heir to the French throne. For more information about the structure and celebration, click here.

"The

Men employed in making Bowers before their Tents..."

Shades

for Common Soldiers

Pennsylvania and New Jersey, 1777 to 1780

Continental soldiers sometimes built bowers for shade and shelter during the warm months (FIG 16). The earliest known use of shades by common soldiers is found in Brig. Gen. John Peter Muhlenberg's 10 August 1777 directive, "Cross Roads" camp, Bucks County, Pennsylvania: "B[rigade]. O[rders]. As it is uncertain how long we shall remain in the Present Encampment the Soldiers are to fix Booths before their Tents to shelter them from the Heat." Terms for makeshift shelters are sometimes problematic: the term booth as used by other soldiers, in quite different situations, describes a crude hut; in this instance the "Booths" were specifically stated to serve as sun protection. In summer 1778 some form of shade was again mentioned in an order for Wayne's Pennsylvanians: "Division Orders, White Plains, August 2, 1778.... Each Regt. will clean away the Stones on their Respective parades this evening, and cover the front of their tents with Green Boughs."9

Although the troops must often have constructed such shades, it is not until two years later we find the next documentary evidence. First, another note of caution concerning nomenclature. On 24 August 1780 Gen. George Washington wrote, "Our Army before now has been almost a whole Campaign without Tents. And this spring were from the 6th. of June till sometime in July, without a single one for either Officers or men (making use of bush Bowers) as a substitute." With the evidence at hand it seems that the shelters mentioned by Washington in 1780 were in fact not "bowers," but brush huts. At this stage of the war either the commander-in-chief's understanding of the terms used for various shelters in the army was imperfect or both bowers and brush huts were being used by the troops; the former contention is more likely. Ens. Jeremiah Greenman's diary shows that brush huts were used by the troops during the time mentioned by Washington. From his 7 June entry noting "the Enemy landed at Elesebeth Town ... [and we] proceeded on towards ... Spring Field in Sight of the Enemy where we halted & formed the Line, where we continu'd in the wrain all Night," until 9 July when he wrote that "we pitched our Tents on a very pleasant hill, after laying without tents from the 7th June," Greenman several times mentioned makeshift shelters, all of them "bush housan."10

Bowers were used later used by Washington's soldiers during summer 1780, but only after tents reached the army early in July. Again, these shades were used in conjunction with tents: Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne's orders, Totaway, New Jersey, 9 July 1780, "As soon as the tents are Pitched and the Bowers made, the Troops will attend to Claning and repearing their Cloths & Arms. Racks or Forks are to be fixed in front of each regt to bear the arms against."11

Virginia Peninsula, 1781

In summer 1781 a detachment of troops commanded by the Marquis de Lafayette operated against British forces commanded by Charles, Lord Cornwallis, on the Virginia Peninsula. When the enemy was in close proximity American forces frequently operated without their baggage train carrying tent-age. The men had to shift for themselves at such times, occasionally sleeping in the open, sometimes building bowers and brush huts for shelter. Lt. Ebenezer Wild, with Vose's Battalion of Lafayette's light troops, left a record of makeshift dwellings built during that time.

29th. [June] ... At sundown we moved back two miles above Bird's [Ordinary], and halted in the woods.

30th. Built bowries and remained on this ground all day.... Our tents and baggage arrived at this place.

Sunday 1st July, 1781. Marched at daylight, and halted at 9 o'clk on a large plain near York river, where we built bush huts (the weather being exceeding warm).

2d. Marched at daylight, and passing by Bird's, turned out of the road ... into the woods to form an ambuscade for a party of the enemy's horse.... But unfortunately they discovered our manoeuvre and made their escape; after which we marched out of the woods and built some bowries, which we lay in till 3 o'clk, when we marched again back to the place we left at daylight this morning.

3d. Marched at 6 o'clk A.M. and proceeded 4 miles, and halted in a field ... where we pitched what tents we had left (the greater part of them being lost).

5th. Marched at eight o'clk A.M., and proceeded half a mile below Bird's, where we halted & built bowries.... At five o'clk we marched one mile further, halted, and built huts. At nine in the evening the troops marched again....

29th. [July], Sunday Struck our tents and bowries for the purpose of airing the ground.12

The shades built in August 1777 and 1778 were described as being in "front of their tents," suggesting a bower like that illustrated in FIG 17. From the above information it is not clear where the 29 July 1781 "bowries," and those constructed in July 1780 at Totaway, New Jersey, were positioned in camp. They may have stood alone, away from the tents, though Lieutenant Wild's mention of taking down tents and bowers "for the purpose of airing the ground" indicates that some shades may have been built differently. One possibility is their being built above the tents; in order to strike tentage the bowers would have had to be dismantled. While Civil War soldiers occasionally built shades over tents, a structure of this type is unlikely in 1781 since we lack evidence of bowers being built over common soldiers' tents at any time during the War for Independence.

Another possibility is that some bowers (like those erected in the absence of tents in June and July 1781) may have been very crude affairs, much like a lean-to, built quickly to provide both shelter and shade for the soldiers. Thus, Wild's "bush huts" may have been enclosed lodges and his "bowries" a combination open hut/shade. This would make sense considering that both were used by Lieutenant Wild and his men on two occasions at different locations the same day; it would also explain the 29 July order to air the ground under the bowers. Those men without tents on 29 July had to construct their own shelters, which may have resembled one built by soldiers in December 1777, described as being "made with two forked saplings, placed in the ground, another [sapling] from one to the other. Against this, fence-rails were placed, sloping, on which leaves and snow were thrown, and thus made comfortable." The "Booths" built for shade in 1777 by General Muhlenberg's troops may also have been lean-tos similar to this.13

Lieutenant Wild's account indicates that while bowers were built primarily for shade, they were occasionally used to provide more substantial shelter, possibly with some variation in construction. Additionally, the diary entries for 2 and 5 July show bowers being so easily and speedily built that their construction and abandonment after a few hours use was a matter of course.

New York, 1782

Shortly after arriving at their new encampment at Verplank's Point in late summer 1782, the soldiers of Washington's army were directed to construct bowers. General orders, Verplanks Point, New York:

Sunday 1st Sept 1782 ... the General is desirous the Troops should make themselves as comfortable as possible while in the Field, The Encampment itself is very pleasing and Healthy, straw will be issued at the Rates of two Bundles Pr tent of this with the Flaggs and Leaves which may be procured convenient Matts or Beding may be formed, Shades or Bowers should also be erected in Front of the tents, in the Construction of which regularity will be extreamly pleasing to the Eye. Vaults [i.e., latrines] must be made in the Rear of the Line & covered every Day....

2d Septr '82 ... the Troops will hasten & compleat their Bowers & acomadations as soon as Possible until Thirsday next their time may be devoted to that Purpose.... the Vaults should be shaded with interwoven Boughs so as to cover them as much as possible from view.14

Although it is possible some earlier bowers were built with "regularity" this is the first mention of uniformity in construction.

Lieutenant Greenman corroborated enactment of these orders:

M[onday] 9. [September 1782]... proceeded up the River to Verplanks Point, where landed the Bagage of the Regmt. & had it carried to the ground alloted for the Regmt. to incamp on & spread the Tents on the ground assigned them. The whole Armys Incampment [is] in one right Line with elegant bowers built before the Tents.15

FIG 17. "The whole Armys Incampment [is] in one right Line with elegant bowers built before the Tents." A representation of how the bowers may have looked. Specifications of January 1781 give the dimensions of a common soldier's tent as "7 Feet Square 7 Feet [in] Height." Illustration by Ross Hamel.

An excellent overall view of this camp is given by the Marquis de Chastellux, who also makes reference to the use of bowers by the French Army. The Marquis

spent a day or two at ... Verplank's Point.... The American camp here, presented the most beautiful and picturesque appearance: it extended along the plain, on the neck of land formed by the winding of the Hudson, and had a view of this river to the south; behind it the lofty mountains, covered with wood, formed the most sublime back-ground that painting can express. In front of the tents was a regular continued portico, formed by the boughs of trees in verdure, decorated with much taste and fancy; each officer's tent was distinguished by superior ornaments. Opposite the camp, and on distinct eminences, stood the tents of some of the general officers, over which towered, predominant, that of General Washington. I have seen all the camps in England, from many of which, drawings and engravings have been taken; but this was a subject worthy the pencil of the first artist. The French camp during their stay at Baltimore, was decorated in the same style.16

In addition to confirming the use of bowers and tents together, the 2 September order is interesting because it mentions another type of makeshift construction (i.e., barriers to shade the latrines, probably from both the sun and the eyes of onlookers) and the recommendation made concerning bedding for the men. (On a side note, the "Flaggs" referred to in the order for 1 September have been defined in Richard M. Lederer, Colonial American English: A Glossary, as "an aquatic plant with long, broad leaves used for mats, roofing, and chair seats. Hence 'flag bottom' and 'flag chair.' In 1634 William Wood wrote, 'In Summer they gather flagges, of which they make Matts for houses.'")

In this same vein, an early-war account illustrates another use for shades: General orders, Continental Army "Head-Quarters, Middle-Brook, June 3, 1777 ... The Brigadiers to have the Springs, adjacent to their several encampments, well cleared and enlarged; placing Sentries over them, to see that the water is not injured by dirty utensils. A board sunk in them, will be the best means to keep them from being muddy, and an arbour over them will serve to preserve them cool."17

The various soldier-built shelters were particularly vulnerable to catching fire, as was the army's tentage. At the 1782 Verplanks Point camp the following order was issued a few days after the men were directed to construct bowers.

The present mode of encampment, tho' extremely ornamental and convenient, may, without the utmost care subject us to the loss of our tents by fire. The Boughs of which the Colonade is composed being so very dry, that a spark of fire or a candle falling among them would not fail to set them instantly in a blaze. The Commander in chief therefore recomends the gratest circumspection to the officers in their Marques and tents, and directs the officers of police to see that the soldiers do not make use of fire or Candles carelessly in theirs.18

Such mishaps did occur from time to time. In Pennsylvania, on 13 December 1776, a Virginia sergeant recorded, "The night past I had the misfortune to have my hut burned and most of everything I had, a pair of new leather breeches, two shirts, stocks, and several things, I being down with the Major and some more gentlemen at supper." Shortly after that, Col. Timothy Pickering wrote in his journal, above Kingsbridge, New York, "January 22d. [1777] Paraded my regiment at daybreak. In the evening, having made a large fire before our hut, some sparks flew upon our roof, covered with oak leaves, and in a minute the whole was in flame; but we lost none of our baggage." In December 1777 Lieutenant Wild wrote of a similar occurrence, noting, "Last night ... two [brush] huts were burnt in our regt."19

Bowers and British Troops, 1776 and 1781

British soldiers began building makeshift shelters as early as 1776. They most often resorted to "wigwams," a popular appelation which probably began as a derogatory term for any type of ad hoc shelter; as the war progressed wigwams (usually some form of brush hut) became customarily adopted as a useful and acceptable alternative to tents.20

Only two mentions of British army bowers during the war have been found, though it is hardly credible that such serviceable and easily constructed shades were not more widely used. On 13 May 1776, Capt. Sir Francis-Carr Clerke, Gen. John Burgoyne's aide-de-camp, described in detail a large shade at Chambly, Canada:

We dine every Day under our Bower, which is much admired here. General Burgoyne gave me the Plan, & I was chief Engineer in the Execution of it. I assure your Lordship that it is quite Arcadian, the Dimensions are thirty by twenty, lofty in Proportion with a covered Roof. The Front is with open Arches & before it added a Colonade, if that is the right Name, however something like the Pantheon the Frame of the Building is finished with strong Timbers, & the whole afterwds. covered with green Boughs, which can be replaced from time to time with very little Trouble.21

In the next instance, the bowers were built by and for common soldiers. Near Newtown, Long Island, Capt. John Peebles, 42d Regiment, noted:

Thursday 14th. June 1781. The Battn. assembled at Newtown Churche & marched from thence about 6 o'Clock, the Country people furnish'd us with as many Waggons as we wanted, as well to get quit of us, as to part with a good grace.

Came to our ground about 9 oclock about a mile to the NW of Bedford, where the Light Infantry were Encamp'd, about which time the 2d. Battn. arrived likewise & drew up on our left facing the Town of N:York ... got new Camp Equipage we have very good dry airy ground but very near a Mile to go for water & not a bush to make a shade near [at] hand.

Sunday 17th. June 1781 ... Battn. Orders to change our ground tomorrow Morning.

Monday 18th. cloudy & cool The Tents struck at Reveilee beating & the Battn. march'd soon after about a mile to the rear to a very good peice of ground where water is at hand, within the old Rebel Line; we face about east, with our left to the head of the Wallabout marsh The Men employed in making Bowers before their Tents.22

Although no eighteenth century illustrations have been found, several from the early nineteenth century show bowers used by civilian workers and a number of paintings and photographs of Civil War soldiers' bowers exist. The latter disclose construction details and shed some light on ways they may have been built by American troops eighty years earlier. The supports used for some of these Civil War bowers were rather substantial, several looking to have been about three inches thick. In both photographs and paintings no stabilizing ropes can be seen; it can only be assumed that the support poles were sunk into the ground at least twelve inches or more. Though ropes may or may not have been used for Revolutionary soldiers' shades, in a large bower or modern reconstruction it may be necessary to incorporate them.23

While not necessarily the first choice for shelter among Revolutionary soldiers (brush huts being more commonly used), depending upon the camp's location, weather conditions, and available materials, bowers were a useful adjunct, and occasional alternative, to tents for shelter.

FIG. 18. Bowers such as these were commonly built by soldiers of both armies in the War for Independence; they were also used by farmers, tavernkeepers, and others in civil society. This one shelters a group of brickmakers, circa 1806. William Henry Pyne, Microcosm or, A Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, and Manufactures of Great Britain in a Series of above a Thousand Groups of Small Figures for the Embellishment of Landscape (first published London, 1806, reprinted New York, Benjamin Blom, 1971), four illustrations of bowers as used by farmworkers, 113, 138.

"The troops hutted with

Rails and

Indian Corn Stocks ..."

Sheds, Planked Huts, and Straw Tents, 1775-1777

In an army newly formed and ill supplied, or one divested of excess baggage, sufficient tentage to cover all of the men was not immediately available. Though brush huts were the predominant ad hoc construct used by soldiers, the first makeshift shelters built in the Continental Army were of wooden planks and other materials taken from buildings and fences in the vicinity of camp. For sake of convenience, we will refer to them as sheds. Reverend William Emerson described American encampments near Boston in 1775:

It is very diverting to walk among the camps. They are as different in their form as the owners are in their dress; and every tent is a portraiture of the temper and taste of the persons who encamp in it. Some are made of boards, and some of sailcloth. Some partly of one and partly of the other. Again, others are made of stone and turf, brick or brush. Some are thrown up in a hurry; others curiously wrought with doors and windows, done with wreathes and withes, in the manner of a basket.... I think this great variety is rather a beauty than a blemish in the army.24

Similar shelters were seen in Virginia during the war's first years. In autumn 1775 the Culpeper County Minute Battalion assembled prior to its departure for Williamsburg. One member of the battalion related that the men "encamped in Clayton's old field. Some had tents, and others huts of plank &c." The following year soldiers of a Virginia Continental battalion also built a plank-covered structure: Head Quarters, Williamsburg, 11 April 1776, "A Subaltern is to detach from his guard a Corpl & six men to the point on Kings below Mrs. Burwells House.... A wooden tent [is] to be sent for the Use of the Corpl on the point of Kings Creek."25

In 1776 static encampments like those surrounding British-held Boston the previous year blossomed around New York City. With the threat of an enemy invasion from Canada, and naval operations against New York, transient camps became more common, and soldier-built sheds were occasionally used. In August 1776 Brewer's Massachusetts Regiment marched from Roxbury to Fort Ticonderoga, a journey of twenty-three days. Although tents accompanied the troops, on at least nine days Corp. Ebenezer Wild and his fellow soldiers made use of some alternate form of shelter for the night, mostly meetinghouses and barns. Only once did Wild mention a makeshift shelter; on 28 August the regiment "marched to the saw mills in Castletown, and built some huts with boards, where we lodged this night." At times sheds may have been built into the ground, as were some winter log huts. In October 1776, near Morris Heights on Manhattan Island, Virginia lieutenant John Chilton noted, "We have just removed from our old encampment about 1/2 Mile into the Woods where we are building like Moonacks [groundhogs] in the ground... [and] send out scouting parties and [t]ake plank (which we want for our hovels)." It is uncertain whether Chilton referred to digging fortifications or living quarters; whatever the case their "hovels" were made of plundered wood.26

American soldiers are known to have built plank huts on several occasions in 1777. Col. Timothy Pickering commanded a regiment of militia from Essex County, Massachusetts. On 19 January 1777, in camp just north of Kingsbridge, New York, he noted, "We retired to quarters. General Lincoln, and son, and myself erected a hut with rails and straw, and lodged in the woods." In September that same year light horseman Robert Treat and his troop marched from Bennington, Vermont, to Stillwater, New York, "There we put up for that Night[,] the best of our Loging was in the Continettle Yard round a haystack nothing to Cover us but the Skeys and the next day we march[ed] to head Quarters / after we got there we had orders to Look out for our selvs... we found Good pasther for our horses and the Capt and ... other offersers thought it best to git a few board [to] make a lettel hut out in [a] field. we Livd there two days."27

British troops also built sheds during the early war years. An officer recounting the 1777 winter spent in New Brunswick, New Jersey, noted:

We expected to have gone into barracks with the Grenadiers, but we were very much disappointed. The men were quartered in barns [the whole winter], and the officers of three Companies [twelve men] in one room ... and half the battalion ordered on picquet on a bleak hill without any cover but some paling and straw made into a shed, a large fire at our feet one side roasted and the other frozen.28

Lt. Loftus Cliffe, 46th Regiment, referred to such shelters in January 1778: "I mount a picket every fourth Day, have then a good Shed over me & fire & am under no apprehension of a Surprise from the Enemy who lye west at Valley Forge about 17 or 18 Miles off." When the situation allowed, sheds were also built in warm weather. Though tents were available in June 1777, on the fourteenth British headquarters directed that "The Men are to Erect sheds with Pailing & Bords The Troops to be Readay to march on the shortest notice." The last part of the order is telling. If a hasty movement was called for, the need to strike tentage and load it onto wagons was precluded by resorting to ad hoc shelters.29

Farmers' fields also supplied building material for British and German soldiers during the Philadelphia campaign. Capt. John Montresor, Royal Engineers: "This day August 25th 1777 [Sir William Howe's army] landed at head of Elk.... The troops hutted with Rails and Indian Corn Stocks, no Baggage or Camp Equipage admitted. Came on about 10 this night a heavy storm of Rain, Lightning and Thunder." Howe's soldiers remained in their leaky shelters for two more days as rain and thunderstorms soaked the area.30

German captain Johann Ewald noted in September 1777, "Our gypsy dwellings ... were mostly nothing but huts of brushwood." Other materials were also used that autumn. Early in the nineteenth century, John F. Watson interviewed inhabitants of Germantown, several of whom described soldiers' huts during the October 1777 British occupation. According to Jacob Miller, who was about sixteen years old at the time, "On Taggert's ground were a great many of the British encamped in huts, made up from the fences, and overlaid with sods." As a boy Abraham Keyser saw, "A large body of Hessians ... hutted in Ashmead's field ... near the woods; their huts were constructed of the rails from fences, set up at an angle of 45 [degrees], resting on a crossbeam centre; over these were laid straw, and above the straw grass sod they were close and warm." A carpenter's apprentice, Benjamin Lehman, recalled that "the British... took up all the fences and made the rails into huts, by cutting down all the buckwheat, putting it on the rails, and ground [sod] over that. No fences remained." Old-age recollections may be suspect, but these are corroborated by New Jersey colonel Elias Dayton, who, on 24 October, observed huts near Philadelphia, on the west side of the Schuylkill River. The British near "Meriam Meeting House ... had begun to build two or three redoubts, and to throw up lines of a considerable extent. They had completed a number of very good huts, built of rails, hay and sods."31

These huts are reminiscent of "hurdled Huts" used by the Allied army (consisting of British and Prussians, along with contingents from several smaller German principalities) in Germany during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). Bennett Cuthbertson described them in his 1768 military manual: "If a Regiment is to Remain very late in the Field, it is more than probable, that an order will be given ... for the Soldiers to hut.... The most expeditious and ready method, is, to provide square hurdles, large enough to cover a Tent, when resting slope ways against the upper edge of each other; they must be above a foot on every side longer than the Tent." (A hurdle was a "portable rectangular frame... having horizontal bars interwoven ... with hazel, willow, etc.")32

While these "hurdles" were stacked directly over soldiers' tents, the materials used for covering them and their advantages over tentage in cold weather echo the 1777 fence-rail huts:

These hurdles and wickers being properly made and fixed, a thick coat of thatch (either straw, sedge, or rushes) is to be laid on them, well secured and bound: nothing can be warmer than these habitations, when the Soldiers are in it, have drawn to the door, and pinned the Tent quite close on every side: huts dug into the earth, or built with sods, are, at an advanced season of the year, extremely damp, and of course unhealthy to the Soldiers; the hurdle ones, on the contrary, are always dry, as the front can be entirely laid open in fair weather, by removing the wicker door, and turning up the bottom of the Tent, in such a manner, that the air may have an [un]interrupted passage round the inside of them.33

The door consisted of "a piece of wicker-work ... fitted to the front."

The 1777 British and German huts were probably meant for long-term occupation, though in the end most were abandoned rather soon after construction. Straw was used, or intended for use, in shelters very early in the Revolution. In "Colledge Camp" at Williamsburg in September 1775, the commander of the 2d Virginia Regiment remarked that "in Case, Tents are ready the Captains are with their Companies Immediately to repair to the Camp, Other wise, Rooms are to be looked out, & if to be had in Town they are to be Quartered in them, till tents can be had or straw ones made to Incamp the Companies." These "tents" were likely made of bundled straw or a frame of planks covered with straw shocks.34

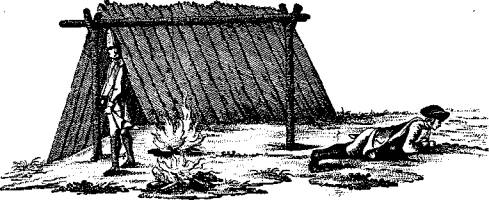

Two postwar drawings show wooden tents in use. A 1788 German military manual clearly illustrates an A-frame structure made with forked uprights and a ridgepole, covered with planks (FIG 19). The same type of shelter is pictured in the background of Charles Willson Peale's painting "The Exhumation of the Mastodon" (1806-1808), an event which took place in early nineteenth-century New Jersey, not far from Philadelphia. Further evidence that most military makeshift shelters had civilian counterparts.35

FIG. 19. Wooden tent pictured in the 1788 German military manual, Was ist jedem Officier waehrend. Courtesy of Charles Beale.

Notes

1.

Sources of makeshift shelter names: "brush Hutt," "Journal of Lieut. William McDowell of the First Penn'a. Regiment, in the Southern Campaign, 1781-1782," in John Blair Linn and William H. Egle, Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution, Battalions and Line 1775-1783, (Harrisburg, 1880), 298-99 (hereafter cited as Linn and Egle, Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution); "bush housen," "buth" (booth), and "housan of branchis & leavs," Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution: An Annotated Edition of the Military Journal of Jeremiah Greenman, ed. Robert C. Bray and Paul E. Bushnell (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1978), 87, 98 (note 131), 174 (hereafter cited as Bray and Bushnell, Diary of a Common Soldier); "hemlock bowhouses," Journal of Jehiel Stewart, 1775-1776, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, Microfilm Publication M804, reel 2290, W25138, Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, DC (hereafter cited as Pension Files, NA); "huts [of] brush and leaves," "Journal of Ebenezer Wild," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 2d ser., 6 (1891): 105 (hereafter cited as "Journal of Ebenezer Wild").2.

R.A. Brock, ed., "Orderly Book of the Company of Captain George Stubblefield, Fifth Virginia Regiment, From March 3, 1776, to July 10, 1776, Inclusive," Virginia Historical Society Collections, n.s., 6 (1887): 186.3.

Regimental orders, 27 May 1777, Order Book of Col. Daniel Morgan's llth Virginia Regiment, New Jersey, 15 May-9 June 1777, Early American Orderly Books 1748-1817, microfilm edition (Woodbridge, NJ, 1977), reel 4, item 45, Collections of The New-York Historical Society; Miscellaneous notes for August 1777, diary end sheets, Diary of John Chilton, captain, 3d Virginia Regiment, A. Keith Family Papers, 1710-1916, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond (hereafter cited as John Chilton Diary, VHS); Joseph Plumb Martin, Private Yankee Doodle A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier, ed. George E. Scheer (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1962), 266 (hereafter cited as Martin, Private Yankee Doodle).4.

Journal of Lt. Erkuries Beatty, 4th Pennsylvania Regiment, 25 September 1779, Journals of the Military Expedition of Major General John Sullivan Against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779 (Auburn, NY, 1887; reprint, Glendale, NY: Benchmark Publishing Co., 1970), 34.5.

Journal of Capt. Daniel Livermore, 3d New Hampshire Regiment, 5 July 1779, ibid., 182.6.

James Thacher, Military Journal of the American Revolution (Hartford: Hurlbut, Williams & Co., 1862), 204.7.

"Journal of Ebenezer Wild," 145, 147.8.

"Itinerary of the Pennsylvania Line From Pennsylvania to South Carolina, 1781-1782,"Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 36 (1912): 281; "Journal of Captain John Davis of the Pennsylvania Line," ibid., 5 (1881): 298.9.

"Orderly Book of Gen. John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, March 26-December 20, 1777," ibid., 34 (1910), 345; Division orders, 2 August 1778, Orderly Book of the First Pennsylvania Regiment, 26 July 1778-6 December 1778, in Linn and Egle, Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution, 2: 297.10.

George Washington to Thomas Blanch, 24 August 1780, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, 39 vols. (Washington: GPO, 1937), 19: 43334 (hereafter cited as Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington); Bray and Bushnell, Diary of a Common Soldier, 17288.11.

Division orders, 9 July 1780, Orderly Book of the First Pennsylvania Regiment, Col. James Chambers, 13 June 1780-5 August 1780, in Linn and Egle, Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution, 2: 545.12.

"Journal of Ebenezer Wild," 143-45.13.

"The Papers of General Samuel Smith; The General's Autobiography," The Historical Magazine, 7, 2d ser., no. 2 (February 1870): 91.14.

General orders, 1-2 September 1782, Order Book, 2 August 1782-14 November 1782, Numbered Record Books Concerning Military Operations and Service, Pay and Settlement Accounts, and Supplies in the War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records (National Archives Microfilm Publications M853), vol. 64, reel 10, target 7, 83-87 (Washington, DC, 1973), Record Group 93, NA.15.

Bray and Bushnell, Diary of a Common Soldier, 258.16.

Marquis de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780-1781-1782 (N.p., 1827; reprint, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1970), 67-68.17.

General orders, 3 June 1777, Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, vol. 8 (1933), 175.18.

General orders, 8 September 1782, ibid., vol. 25 (1938), 138-39.19.

"The Revolutionary War Journal of Sergeant Thomas McCarty," ed. Jared C. Lobdell, Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 82, 1 (January 1964): 40; Octavius Pickering, The Life of Timothy Pickering, 2 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1867), 1:100 (hereafter cited as Life of Timothy Pickering); "Journal of Ebenezer Wild," 105.20.

"17. [September 1776] ... Very wet m[ornin]g. p.m. Cleared. No tents, built wigwams ...," "Bamford's Diary: The Revolutionary Diary of a British Officer," Maryland Historical Magazine, 27 (September 1932): 9; "Thursday 18th [June 1778] ... the Troops march'd to within 2 miles of Haddonfield where they Encampd in the usual manner, vizt. Wigwams...," Journal of John Peebles, Scottish Record Office, Edinburgh; Cunninghame of Thorntoun Papers (GD 21), Papers of Lt., later Capt., John Peebles of the 42d. Foot, 1776-1782, incl. 13 notebooks comprising his journal, book 6, 1778, Monmouth Campaign, ibid. (hereafter cited as John Peebles Journal, Scottish Record Office). Concerning the British army commanded by Charles, Lord Cornwallis, in Virginia, spring and summer 1781: "Our encampments were always chosen on the banks of a stream, and were extremely picturesque, as we had no tents, and were obliged to construct wigwams of fresh boughs to keep off the rays of the sun during the day," Samuel Graham, 76th Regiment, "An English Officer's Account of his Services in America 1779-1781. Memoirs of Lt.-General Samuel Graham," Historical Magazine (1865): 269.21.

Don N. Hagist, "Notes and Queries," The Brigade Dispatch, 29, no. 3 (Autumn 1999): 28 (original citation given as "Letters to Lord Polwarth from Sir Francis-Carr Clerke, Aide-de-Camp to General John Burgoyne," New York History, 79, no. 4 [October 1998]: 413). Captain Sir Francis-Carr Clerke was in the 3d Regiment of Foot Guards.22.

Journal entries, 14, 17 and 18 June 1781, John Peebles Journal, Scottish Record Office, book 12, pp. 37, 38.23.

William Henry Pyne, Microcosm or, A Delineation of the Arts, Agriculture, and Manufactures of Great Britain in a Series of above a Thousand Groups of Small Figures for the Embellishment of Landscape (London, 1806; reprint, New York: Benjamin Blom, 1971), four illustrations of bowers as used by farmworkers, 113, 138. In the American Civil War (1861-1865) large bowers were commonly used for outdoor offices, dining or rest areas, or to shade officers' and soldiers' tents. Pictorial evidence of the extensive use of freestanding bowers by both sides in the war is overwhelming. See also John U. Rees, "'Shebangs,' 'Shades,' and Shelter Tents: An Overview of Civil War Soldiers' Campaign Shelters," (unpublished ms., author's collection).24.

Herbert T. Wade and Robert A. Lively, "this glorious cause ...": The Adventures of Two Company Officers in Washington's Army (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958), 25.25.

John R. Elting, ed., Military Uniforms in America, The Era of the American Revolution, 1755-1795 (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1974), 110; Charles Campbell, ed., The Orderly Book of That Portion of the American Army Stationed At or Near Williamsburg, Va., Under the Command of General Andrew Lewis From March 18th, 1776 to August 28th, 1776 (Richmond: privately printed, 1860), 20-21.26.

"Journal of Ebenezer Wild," 78-83; John Chilton to his brothers, 6 October 1776, John Chilton letters, A. Keith Family Papers, 1710-1916, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond; "Moonacks," see monack in Richard M. Lederer Jr., Colonial American English (Essex, CT: Verbatim, 1985), 150.27.

Life of Timothy Pickering, 2: 99; Robert Treat's Journal, Capt. Isaac Treat's Co., Major Elijah Hyde's Troop or Regiment of Connecticut Light Horse, 19 August to 30 September 1777, reel 2411, Pension Files, NA. See also Fred Anderson Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units (Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 1972), 50.28.

Martin Hunter, The Journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter (Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Press, 1894), 24.29.

Loftus Cliffe to "Bat," 20 January 1778, Loftus Cliffe Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; General orders, 14 June 1777; Regimental orders, 19 June 1777, British Orderly Book (40th Regiment of Foot), 20 April 1777 to 28 August 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington, 1961), series 6B, vol. 1, reel 117, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington.30.

"Journal of Captain John Montresor, July 1, 1777 to July 1, 1778," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 5 (Winter 1881): 409.31.

Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, ed. and trans. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 80; John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: John Penington and Uriah Hunt, 1844), 2: 40, 55, 59; "Papers of General Elias Dayton," Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 3 (1848-1849): 187.32.

Bennett Cuthbertson, System for the Compleat Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry (Dublin, 1768), 40-41; The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Hurdle."33.

Cuthbertson, op. cit.34.

Brent Tarter, ed., "The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment, September 27,1775-April 15, 1776," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 85, no. 2 (April 1977): 159.35.

Wooden tent or plank hut illustrated in Was ist jedem Officier waehrend eines Feldzugs zu wissen noethig ["What it is necessary for each officer to know during a campaign"] (Carlsruhe, 1788), pl. 9; William Ayres, ed., Picturing History: American Painting 1770-1930 (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1993), 56-57.